From Consulting to the House of Lords: A Conversation with Lord Moynihan

May 7, 2025

Baron Moynihan of Chelsea, OBE (Jon Moynihan) is the former CEO and Executive Chair of PA Consulting Group, the successful global management consultancy firm. He is highly experienced, with degrees as far afield as Balliol College Oxford and MIT and consulting posts at McKinsey & Company in Amsterdam and First Manhattan Consulting Group in New York. He is now a member of the UK’s House of Lords and an active investor. PA was a value creation success story for the broad group of employees who enjoyed ownership, attracting buyers such as Carlyle Group and eventually Jacobs Engineering.

Jon’s approach to incentive compensation contributed to the success of PA, which is an element of our discussion. But first, we talked about his latest work: a book in two volumes on growth. Having read Jon’s book, Farient Advisors UK partner Simon Patterson embarked on a wide-ranging discussion with Jon, exploring the importance of growth — a key ingredient behind successful firms and prosperous countries — and how to create the conditions for growth.

As the Financial Times wrote, his work provides: ‘a rare, detailed diagnosis and set of recommendations to get [the UK] back on course. Moynihan does not mince his words, and while some may disagree with his assessment of Britain’s problems — and the solutions — this is a highly valuable contribution to a debate often short on detail’.

Simon Patterson: Your book was recently cited by Allister Heath in a front-page article in The Daily Telegraph (29/1/25) as follows: “[the Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel] Reeves should read and adopt Jon Moynihan’s manifesto, as set out in his brilliant two-volume [book] ‘Return to Growth‘. What you say is that growth is vital to any economy, and particularly that of the UK. Growth funds the services we need and creates the opportunities we aspire to.

Lord Moynihan: You work with larger corporations, but a tremendous amount of growth comes from entrepreneurs setting up businesses, often one- or two-person businesses, or SMEs with 10 to 200 employees. Governments can create economic conditions that make those companies add or lose employees by increasing a given tax. These are precarious times for SME businesses, many live on the margin. If they lose money, they quickly go out of business. One cannot go on borrowing from the bank, dipping into savings, or borrowing from family or friends to keep going. If a business is losing money — due to increased national insurance contributions, for example — there is no choice but to cut employment costs to return to a profitable position. Conversely, if the government helps businesses, they can hire new people.

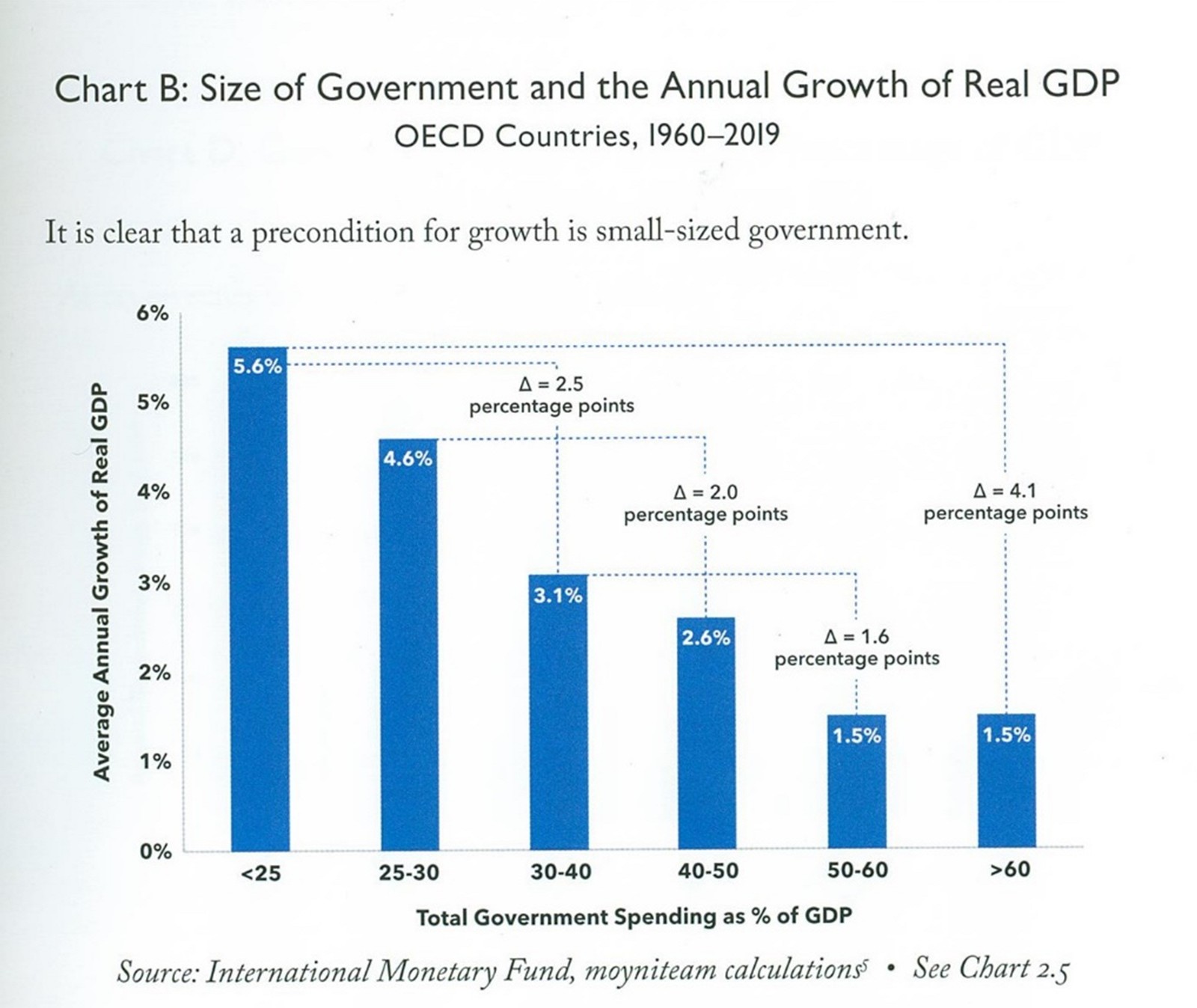

Simon: The prescription in your book is smaller government, lower taxes, less regulation.

Lord Moynihan: The reason taxes go up, resulting in fewer people being employed, is that spending has increased. The government is told by its advisers, particularly the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), that if they raise taxes, the bond markets will react badly. They will be forced into a cul-de-sac: governments can’t spend their way to growth because to fund that spending, they need to increase taxes, suppressing growth — the equivalent of saying, ‘You’re in a hole, please keep digging’.

Simon: In other words, the wrong way around.

Lord Moynihan: Governments of all stripes say their priority is economic growth. Some may say they want the world’s economies not to grow — because of a net-zero goal or attitude toward ESG — but governments tend to agree that growth is the number one priority. The problem is that most have no plan to achieve growth.

Creating growth is straightforward: lower government spending, lower taxes, and reduce regulation. The book demonstrates this. Ironically, recent experience has shown that governments often believe in regulating more.

Simon: Do you think creating shareholder value is easier if you’re a large rather than a small company?

Lord Moynihan: It depends on what sector you’re in and what strategies you adopt. A lot of my work was in mergers and acquisitions. Some of our early successes were from taking a large conglomerate and persuading it to sell off a third or half of its businesses that were just not well situated to create shareholder value. Sometimes, the share price of very large companies would triple.

Another way is incentivizing people to do the right things and create shareholder value.

Simon: Yes. Incentives work, but creating value is much more difficult than people think. We may look at a headline figure for an executive’s pay package and say, ‘Gosh, the head of XYZ is paid lots of money, isn’t that terrible?’ They may well be delivering tremendous shareholder value and doing a difficult job. Creating value means finding investments that will offer returns higher than the cost of capital. Over time, competitors jump in, and it becomes more difficult to deliver those superior returns.

Lord Moynihan: In the end, everything in a truly competitive industry should return to a cash flow break-even situation, which is not what the shareholders want. The place to be if you want to create shareholder value is on the growth part of the S curve (finding investments with a positive return).

Competition should bring costs to the consumer down. Still, large companies can take shortcuts, achieving shareholder value by lobbying for more favourable circumstances, such as barriers to keep out competitors. There’s indeed a great deal of growth in the US, and they are getting richer and richer than the British every year, but the US is plagued by those trying to reduce competition for their ends, even in small ways. For example, a small business braiding people’s hair in your front room increases economic growth, but you can’t do that unless you get a state license. It is a classic example of people already in that business trying to keep others out.

Simon: The London taxi market might be an example.

Lord Moynihan: In the end, Uber changed the game. Hospitals in the US are another example. More hospitals would probably improve healthcare delivery, but who objects to establishing a new hospital? All the existing hospitals. It’s challenging to build new hospitals, and one of the reasons why healthcare is so expensive.

Simon: On executive pay, do you think a more readily available supply of executive talent would drive down the cost of executives? Do you believe succession planning, the supply side as it were, will lower executive pay growth?

Lord Moynihan: It may, but executive pay growth was partly due to being told that one needs to be in the top quartile of pay relative to peers to attract top talent. That created a leap-frogging effect. It might also have been because of a belief that the bigger the company, the more an executive should be paid. That meant chief executives were incentivized to merge with or buy other companies to get bigger and be paid more. It is even possible that drove an M&A boom, which destroyed shareholder value (buying other companies virtually always destroyed shareholder value, it seems).

Well, PA couldn’t play that game because, in the consulting industry, we were competing with very successful companies. Salaries were getting higher and higher, so we said we would do something different. We will pay in the bottom quartile of salaries but with high bonuses for success. Consequently, when we were recruiting, people never joined for the salary. We said we’ll pay you at the lower quartile in salary, but we’ll pay you huge bonuses if you meet well-defined metrics. You’d call it creating shareholder value.

Simon: You’re creating a surplus?

Lord Moynihan: Precisely. We had a share price that was just the book value that increased by the surplus amount each year. The share price went up 100-fold. People who stuck with our system all became tremendously rich. We created hundreds of millionaires, and [when they] sold the company, it created quite a few deci-millionaires. The pay plan worked beautifully, but we had to persuade people to consider the long-term.

Simon: It must have been quite a controversial approach. Were you keeping base pay a small proportion of the total reward and at the lower quartile of peers?

Lord Moynihan: Yes.

Simon: An example of an incentive programme with many of the best characteristics is probably a management buyout, where employees and owners are in the same boat, and everyone’s aligned.

Lord Moynihan: Management buyouts usually only give shares to the top half dozen or so of management. I always took the view as a private professional services firm that the company should be owned by all its employees so that everybody had the opportunity, including people down in the ranks, to make money if they stuck with the shareholder scheme (rather than selling off their shares as soon as they got them). It could be argued that I was not hard-hearted enough because the top managers make the most difference, but it did ensure that every single employee could think, ‘It’s my firm. I’m an owner’.

© 2026 Farient Advisors LLC. | Privacy Policy | Site by: Treacle Media